Tuning Tips and Advice

- A collection of tips and advice for you to improve query performance

- Learn about USE KEYS, partial indexes, covering indexes, prepared statements, and more

- Explore common practices that should be avoided in production, like using a primary index or a LIKE statement

Tip 1: Use USE KEYS

If you know the Document Id/Key of the document, you should leverage the USE KEYS clause. This bypasses the Index Service (hence bypassing network, scans, index results and processing) - it's the closest thing you have on the N1QL side comparable to a KV fetch. The optimizer will use a KeyScan when you use the USE KEYS instead of an Index or Primary Scan. When the key is known and returning the entire document is required, always preference USE KEYS over a META().id index scan.

SELECT * FROM `travel-sample` USE KEYS ["landmark_37588"];You can specify multiple values in USE KEYS if you are querying for multiple documents.

SELECT * FROM `travel-sample` USE KEYS ["landmark_37588", "landmark_37603" ];JOIN operations are also done using the document keys.

SELECT * FROM ORDERS o INNER JOIN CUSTOMER c ON KEYS o.id;

SELECT * FROM ORDERS o USE KEYS ["ord:382"] INNER JOIN CUSTOMER c ON KEYS o.id;As this query is performing a KV GET() via N1QL, it would be even more performant to bypass N1QL altogether and issue a KV GET() directly via the SDK. bucket.get("landmark_37588")

Note that when selecting specific field(s), a covered index scan may be faster than performing the data service fetch when working with large documents or a long list of keys.

Tip 2: Do not Index Values that are an EQUALITY predicate of the Index

Remove any index keys/expressions that are listed in both the index and the indexes WHERE statement as an equality predicate. These values would have zero cardinality and do not need to be indexed as they would result in slower IndexScans, they simply need to prevent documents who do not satisfy the condition as true from being added to the index. The query/index services are intelligent enough to understand a query and automatically cover values that are present as an equality predicate in the index.

Consider the following query:

SELECT userId, firstName, lastName

FROM ecommerce

WHERE docType = "user" AND username = "johnsmith21"Now consider the following indexes, all of which will satisfy the query above:

CREATE INDEX idx_usernames ON ecommerce(docType, username)This index emits both docType and username into the index. Not only is username more unique, but you would expect that this index only contained just "user" documents. However, this index would contain an entry for every single document where the document had a docType property, regardless of whether or not it has a username property as only the leading key needs to qualify. Think of the leading key having a WHERE docType IS NOT MISSING statement.

CREATE INDEX idx_usernames ON ecommerce(username, docType)This index would successfully limit the indexes scope to just documents that contained a username property, but again this is not guaranteed. we could filter the index by adding a WHERE docType = "user" predicate:

CREATE INDEX idx_usernames ON ecommerce(username, docType)

WHERE docType = "user"However, by having the docType emitted into the index when it will only be a single value, it is just wasted bytes.

CREATE INDEX idx_usernames ON ecommerce(username)

WHERE docType = "user"This is the best choice of all of the indexes above, as it will filter out any documents that do not satisfy WHERE docType = "user" and only index the remaining documents that contain a username property.

Tip 3: Every Index should be Filtered i.e contain a WHERE clause

Often times referred to as "Partial Index", filtered indexes are an index on a subset of documents in the keyspace which are relevant to the query being executed. The result is a smaller index, which results in faster scans, yielding faster response times.

CREATE INDEX idx_cx3 ON `travel-sample` (state, city, name.lastname)

WHERE type = 'hotel'

CREATE INDEX idx_cx4 ON customer (state, city, name.lastname)

WHERE type = 'hotel' and country = 'United States' AND ratings > 2Tip 4: Index Key Order and Predicate Types

The order of index keys, as well as the cardinality (uniqueness) of the values for a specific key/expression, can have a dramatic affect on query performance. Index keys should be first ordered based on the queries predicate types in the following order:

- EQUALITY

- IN

- LESS THAN

- BETWEEN

- GREATER THAN

- Array predicates

- Look to add additional fields for the index to cover the query

For keys who share the same predicate type, cardinality comes into play. As a general rule of thumb, order keys from left to right based on highest cardinality (most unique) to lowest cardinality (least unique) when they share the same predicate type. Note that the query predicates do not need to be listed in the order in which they are listed in the index, the query planner determines this automatically.

Consider the following query and index:

SELECT cid, address

FROM customer

WHERE type = 'premium'

AND state = 'CA'

AND zipcode IN [29482, 29284, 29482, 28472]

AND salary < 50000

AND age > 45CREATE INDEX idx_orders ON customer(state, zipcode, salary, age, address, cid)

WHERE type = 'premium'Even though zipcode is more unique than state, it is being queried using an IN statement which is the equivalent of an OR. It is more efficient to reduce the index entries first by state then by zipcode, however if our primary access pattern was zipcode = 29482, then we would want to list it first.

Tip 5: Index to Avoid Sorting

Each index stores data pre-sorted by the index keys, matching the keys in the ORDER BY and leading N keys will avoid sorting. When exploiting the index order, the index keys should be added after all predicates and before any additional values that may be used to cover the query.

Take a scenario where you want to retrieve the order history for a given user, consider the following index and query:

CREATE INDEX `idx_order_history` ON `ecommerce` (

userId, orderDate, orderTotal, orderId

)

WHERE docType = "order"SELECT orderId, orderDate, orderTotal

FROM ecommerce

WHERE docType = "order" AND userId = 123

ORDER BY orderDate DESCIf you examine the EXPLAIN plan for the query near the bottom you will see:

{

"#operator": "Order",

"sort_terms": [

{

"desc": true,

"expr": "cover ((`customer`.`orderDate`))"

}

]

}The Order operator takes all of the documents from the previous operator (IndexScan) and must loop over all of the records and sort them in-memory based on the ORDER BY statement. Data is pre-sorted ASC by default, with the previous index the ASC is implied but would look like:

CREATE INDEX `idx_order_history2` ON `customer` (

userId ASC, orderDate ASC, orderTotal ASC, orderId ASC

)

WHERE docType = "order"Knowing that we want our result ordered by the orderDate DESC, we can inform the indexer to store the data in the order in which we will use it:

CREATE INDEX `idx_order_history_sorted` ON `ecommerce` (

userId, orderDate DESC, orderTotal, orderId

)

WHERE docType = "order"Now if we issue an EXPLAIN on the query, you will see the "Order" operator is missing as it is not needed since the result is already in the appropriate order.

Tip 6: Use Covering Indexes

Covering Indexes are indexes which contain all of the query predicates (WHERE), all of the returning values (SELECT ...) and any other processed attributes. When the index contains all of these values, it "covers" the query and the Query service does not need to go-to the Data service to obtain values for those fields. Covering indexes make queries efficient since it bypasses the "FETCH" from the Data service saving a significant amount of data transfer and processing. Both the Final Project and Filtering can be "covered" if an index is created appropriately.

Consider the following index:

CREATE INDEX idx_cx3 ON customer(state, city, name.lastname)

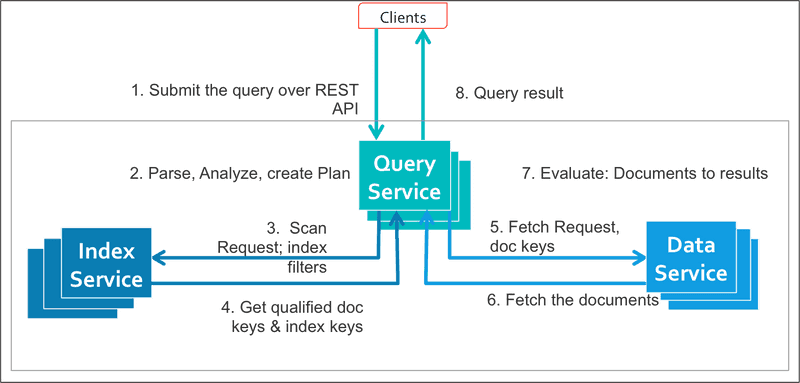

WHERE status = 'premium'The following diagram illustrates the query execution workflow for a query that is not "covered":

SELECT *

FROM customer

WHERE state = 'CA' AND status = 'premium'When performing a SELECT *, a data service fetch will always be required, and the query cannot be covered.

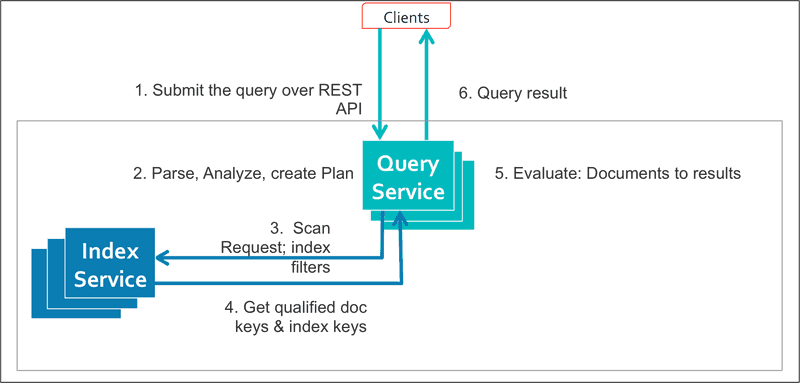

The following diagram illustrates the query execution workflow where the query is covered:

SELECT status, state, city

FROM customer

WHERE state = 'CA' AND status = 'premium'As you can see in the second diagram, a well-designed query that uses a covering index avoids the additional steps to fetch the data from the data service. This results in a considerable performance improvement.

We can verify that a query is "covered" by reviewing the explain plan:

{

...

"~children": [

{

"#operator": "IndexScan3",

"covers": [

"cover ((`customer`.`state`))",

"cover ((`customer`.`city`))",

"cover (((`customer`.`name`).`lastname`))",

"cover ((meta(`customer`).`id`))"

],

"filter_covers": {

"cover ((`customer`.`status`))": "premium"

},

...

}

]

}It is important to note that a "FETCH" operation is not necessarily a bad thing, and every query does not always need to be "covered". Covering indexes offer the performance benefit of having all of the data in a single place and avoid a scatter-gather (i.e. fetches), but a covering index could potentially be fairly large and should be properly sized. A query which performs an IndexScan and returns a few records then performs a fetch, might be perfectly acceptable and meet SLAs. However, a query that returns tens or hundreds of thousands of rows and has to perform a fetch, could have a dramatic effect on system performance.

Tip 7: Never Create a Primary Index in Production

Unlike relational databases, Couchbase and N1QL do not require a primary index as long as the query has a viable secondary index to access the data.

A primary index scan is analogous to a full table scan in relational database systems. However, where a table scan stops at the "table", a primary index scan will perform the equivalent of a full database scan. N1QL will retrieve every document ID in the entire keyspace from the primary index, then fetch each document in the bucket and finally performing any predicate-join-project processing.

When a primary index is present, even though it may never be "intended" to be used, it acts as a fallback for any query who does not have a satisfying index at execution time. Think failure scenarios, if the queries qualifying index(es) go offline for whatever reason (i.e. node failure) and a primary index exists, it will be used, which could cause unintended and unexpected side-effects.

Tip 8: Avoid "docType" Only Index

A keyspace (bucket) in Couchbase is a logical namespace for one or more types of documents. Standard practice in Couchbase is to ensure that each document has a common docType, type, _class, etc. property that identifies the model/purpose of the document. This property is not only a good practice it allows for efficient indexing (i.e. Partial Index).

While filtering on the docType is strongly encouraged as it creates a partial index on a subset of documents, creating an index on the docType as a leading or stand-alone index key is inefficient and has extremely low cardinality.

CREATE INDEX `idx_docType` ON `bucket` (`docType`)Indexes like this can inadvertently cause slow-performing queries and unexpected explain plans. For example, it increases the likelihood of an IntersectScan. More importantly though, if you've established the use of a docType property on each of your documents, more than likely developers writing N1QL statements will add that as a predicate to each of their queries, i.e.:

SELECT *

FROM bucket

WHERE docType = "user" AND username = "johnsmith32"Just as a primary index can be inadvertently used as a fallback when expected indexes are not found and cause potentially a high number of "FETCH" operations, a docType index can do exactly the same thing and this is why it should be avoided.

Tip 9: Partition Indexes

When an index is created, the entire index only exists on a single node (replicas excluded). If the index grows in size and can no longer fit into memory in the case of MOI indexes, or the resident ratio drops low in the case of Standard GSI, you have to either add more resources to the node or you can partition the index.

The process of index partitioning involves distributing a single large index across multiple index nodes in the cluster.

Prior to Couchbase Server 5.5 this was achieved by creating multiple smaller range partitioned or partial indexes. The following query is our example:

SELECT userId, firstName, lastName

FROM ecommerce

WHERE docType = 'user' AND LOWER(username) = 'johnsmith32'The following is the initial index that is used to cover the query:

CREATE INDEX idx_users ON ecommerce(LOWER(username), userId, firstName, lastName)

WHERE docType = 'user'Over time the index grows in size and might not be performing as expected, can no longer fit on a single node, etc. and needs to be partitioned across multiple nodes:

CREATE INDEX idx_users_AtoM ON ecommerce(LOWER(username), userId, firstName, lastName)

WHERE docType = 'user' AND LOWER(username) >= 'a' AND LOWER(username) < 'n'

WITH { "nodes": ["index_host1"]}

CREATE INDEX idx_users_NtoZ ON ecommerce(LOWER(username), userId, firstName, lastName)

WHERE docType = 'user' AND LOWER(username) >= 'n' AND LOWER(username) < '['

WITH { "nodes": ["index_host2"]}The same query above works without any changes. Indexes can be partitioned in an infinite number of ways. As of Couchbase Server 5.5+ you can define a single index, the partitioning strategy/keys as well as the number of partitions (16 by default) to create and we'll manage the distribution across the cluster automatically for you. Index Partitioning can be implemented by specifying the [PARTITION BY] clause.

CREATE INDEX idx_users ON ecommerce(LOWER(username), userId, firstName, lastName)

WHERE docType = 'user'

PARTITION BY HASH(LOWER(username))

WITH { "num_partitions": 10 }Index partitioning has the benefit of "Partition Elimination", where the query planner understands that WHERE ... LOWER(username) = 'johnsmith32', is an equality and it knows which of the 10 partitions that indexed value lives on, and will scan just that single partition. Be sure to evaluate the key/expressions that you're using for partitioning as it can have an impact on the scans.

Tip 10: Avoid the use of SELECT *

Many developers or frameworks will use SELECT * FROM ... as much simpler and less work than typing out individual property SELECT orderId, orderDate, orderTotal FROM .... However, in general, this is not a wise thing to do regardless of the database being used, and in some situations, it can have serious performance implications.

Using SELECT * returns all of the properties for each document. Oftentimes a query does not actually need all of the properties, only a select few. This causes unnecessary I/O, resulting in a larger payload size that must be transferred across the wire back to the application, where a smaller payload is more performant.

The most important reason to not use SELECT * is you are limiting what the query optimizer can do to pick more appropriate indexes (i.e. a covering index). When SELECT * is used, no matter what, 100% of the time a "FETCH" operation will be performed and it is impossible to further optimize the query without changing the underlying code / N1QL statement.

Consider the following scenario, where you want to retrieve all of the airlines for a given country and use the id, name and callsign properties. Initially, our index might look like:

CREATE INDEX `idx_airline_country` ON `travel-sample` (country)

WHERE type = 'airline'Now compare the following queries:

SELECT *

FROM `travel-sample`

WHERE type = 'airline' AND country = 'United States'SELECT id, name, callsign

FROM `travel-sample`

WHERE type = 'airline' AND country = 'United States'Both queries ultimately achieve the result and based on our initial index both queries would perform a "FETCH" operation, because of * in query one, and because query two contains properties that are not in the index. Hypothetically let's say that this query is performed 10 times per second, the index may be perfectly fine and meet SLAs.

You have appropriate monitoring and profiling in place. Over time our application becomes more and more popular, and our query is now being performed 1,000 times per second. Originally, both queries returned 127 records, and a "FETCH" was being performed where 127 docs * 10qps = 1,270 get ops/sec, but is now 127 docs * 1000qps = 127,000 get ops/sec. This is causing system performance issues and you realize that improvements need to be made and the query needs a covering index, the profile of the second query tells you exactly what fields need to be covered and you create the following index in production:

CREATE INDEX `idx_airline_country_cvr` ON `travel-sample` (country, id, name, callsign)

WHERE type = 'airline'If you were using the second query, the number of gets/second would go from 127,000 to 0 and you were able to achieve this without a single code change or deployment to the application. However, if you were using the first query this index would have not offered any performance benefit, the application code would have to be updated and then deployed to see the performance gains.

Tip 11: Avoid the use of USE INDEX

When specified the USE INDEX clause hints to the query optimizer that the index(es) listed should be preferred. The query optimizer is a rule-based optimizer, and will generally pick the most appropriate index to satisfy a query. Additionally, with every release of Couchbase, there are improvements made to the optimizer, making it more efficient.

If a USE INDEX(...) is specified it couples code and operations. Meaning the index that is specified, cannot be dropped without a code change, as the code is expecting the index to be there and if it is not this would result in an error. Moreover, you cannot optimize the index that is referenced without dropping it first which would result in a period of downtime while the index is being built and the creation of a more optimized index wouldn't yield any benefit either as it would not be preferred.

The use of the USE INDEX() statement can be beneficial with the elimination of IntersectScans but should be done with caution for the reasons listed above.

The

USE INDEX(...)clause can accept a comma-delimited list of indexes.

Tip 12: Pushdown Pagination to the Index

Optimizing pagination queries is usually the most critical part of tuning. Exploiting index ordering is even more beneficial when paginating. Both OFFSET and LIMIT are attempted to be pushed down to the indexer whenever possible, this depends on a few different factors:

- If the whole predicate (

WHERE) can be pushed down to a single index (i.e. all index keys exist) - An IntersectScan is not being performed

- If an

ORDER BYclause is used, the index keys must be in the same order - There is no

JOINclause

If all of these are true then the LIMIT and OFFSET are pushed to the indexer, otherwise they are applied by the query service after all IndexScans are performed. Take the following index for example:

CREATE INDEX idx_products ON ecommerce (

productCategory, productName, productPrice, productId

)

WHERE docType = 'product'This query retrieves all of the products sorted by the productName property and exploits the index order so LIMIT and OFFSET are pushed down to the indexer.

SELECT productId, productName, productPrice

FROM ecommerce

WHERE docType = 'product' AND productCategory = "Electronics"

ORDER BY productName ASC

LIMIT 100

OFFSET 300This can be verified by examining the EXPLAIN plan of the query, in the IndexScan3 #operator will show both of the "limit" and "offset" properties, indicating that they were pushed down to the indexer.

{

"#operator": "IndexScan3",

...

"index": "idx_products",

"limit": "100",

"offset": "300",

...

}Now if we adjust the query to sort by productPrice DESC.

SELECT productId, productName, productPrice

FROM ecommerce

WHERE docType = 'product' AND productCategory = "Electronics"

ORDER BY productPrice DESC

LIMIT 100

OFFSET 300The query is still covered, as before but now the "Limit" and "Offset" are pushed to the bottom of the Sequence and are the last thing to happen before the final projection:

[

...

{

"#operator": "Order",

"limit": "100",

"offset": "300",

"sort_terms": [{

"desc": true,

"expr": "cover ((`customer`.`productPrice`))"

}]

}, {

"#operator": "Offset",

"expr": "300"

}, {

"#operator": "Limit",

"expr": "100"

}

]LIMIT and OFFSET are generally the go to for database pagination and Couchbase Server has many optimizations that make these operations really fast. There is one drawback to limit/offset pagination in any database and that is the greater the offset, the longer the initial index scan has to traverse the index before the limit can be implied. Oftentimes this is negligible, however, if you want to squeeze every last bit of performance out of pagination there is another approach called KeySet Pagination.

Tip 13: Use Query Bindings

It is the responsibility of the application to sanitize and inspect dynamic/input data before sending it to the database. If an application uses this input to dynamically construct a query, it is opening the database to SQL injection attacks.

def airports_in_city(city):

query_string = "SELECT airportname FROM `travel-sample` WHERE city="

query_string += '"' + city + '"'

return cb.n1ql_query(query_string)This is insecure as any value or N1QL statement could be passed as city. N1QL allows the use of placeholders to declare dynamic query parameters. Query parameters (named or positional) allow your application to securely use dynamic query arguments for your application.

Implement named or positional parameters for all dynamic query arguments.

def airports_in_city(city):

query_string = "SELECT airportname FROM `travel-sample` WHERE city=$1"

query = N1QLQuery(query_string, city)

return cb.n1ql_query(query)Not only is this more secure, but it also simplifies query profiling and tuning, while the same statement is issued with different parameters, it can be profiled as the same.

Tip 14: Combine Indexes with Shared/Common Index Keys

It can be an easy habit to get into of optimizing every query and have a 1:1 ratio for the query to index. This is not necessary and can be avoided by expecting common leading keys of various indexes and combining multiple indexes into a single index that can service multiple queries. Take the following queries an example:

SELECT orderId, orderDate, orderTotal

FROM ecommerce

WHERE docType = 'orders'

AND billing.country = 'US'CREATE INDEX idx_orders_country ON ecommerce (billing.country)

WHERE docType = 'orders'SELECT orderId, orderDate, orderTotal

FROM ecommerce

WHERE docType = 'orders'

AND billing.country = 'US'

AND billing.state = 'CA'CREATE INDEX idx_orders_state_country ON ecommerce (

billing.state, billing.country

)

WHERE docType = 'orders'SELECT orderId, orderDate, orderTotal

FROM ecommerce

WHERE docType = 'orders'

AND billing.country = 'US'

AND billing.state = 'CA'

AND orderTotal >= 1000CREATE INDEX idx_orders_country ON ecommerce (

billing.state, billing.country, orderTotal

)

WHERE docType = 'orders'All of these indexes can be combined into a single index. It should be pointed out in this example, billing.country is the first index key, as the query that uses it expects billing.country to be the leading key of the index, this may or may not have an effect on SLAs and should be tested as billing.state has a higher cardinality than billing.country but may be negligible.

CREATE INDEX idx_orders_country ON ecommerce (

billing.country, billing.state, orderTotal

)

WHERE docType = 'order'Tip 15: Use Prepared Statements

When a N1QL statement is sent to the server, the Query service will inspect and parse the string, determining which indexes to query, ultimately defining a Query Plan to optimally satisfy the statement. The computation for the plan adds some additional processing time and overhead for the query.

Often-used queries can be prepared so that the computed plan is generated only once. Subsequent queries using the same query string will use the pre-generated plan instead, saving on the overhead and processing of the plan each time. Parameterized queries are considered the same query for caching and planning purposes, even if the supplied parameters are different.

There are two approaches to implementing prepared statements, choose one that best fits your environment.

SDK Prepared Statements

This method of prepared statements sets the adhoc = false option for a given query. The SDK will internally prepare the statement and store the plan in an internal cache specific to that SDK instance. After the statement has been initially prepared the first time, subsequent calls to the same statement will pass the prepared plan to the Query service, eliminating the inspection, parsing, and planning steps and start executing immediately.

query = N1QLQuery("SELECT airportname FROM `travel-sample` WHERE country=$1", "USA")

q.adhoc = FalseNamed Prepared statements

This method of prepared statements is similar to the previous option but instead of the SDK managing the planning of the queries, it would be managed by the application or through an external process.

First, the query has to be prepared by using a PREPARE Statement

PREPARE unique_name_for_query FROM

SELECT airportname FROM `travel-sample` WHERE country=$1Once the query has been prepared, the query plan is cached in the Query service and can be executed by using an EXECUTE Statement.

query = N1QLQuery("EXECUTE unique_name_for_query", "USA")The tradeoff is there is a single cached plan that can be used by many clients, however, the lifecycle of the plan must be maintained. For example, if the plan doesn't exist an error will be thrown, that would need to be trapped and then re-prepare the query and execute again.

Tip 16: Avoid IntersectScans

An IntersectScan is when two or more indexes are used to satisfy a query. This results in two or more separate IndexScan operations, each returning back qualifying results (i.e. meta().id) and then intersecting the scans together only returning results that are present in both. Consider the following query and indexes:

SELECT *

FROM `travel-sample`

WHERE type = "landmark" AND activity = "drink" AND country = "France"CREATE INDEX `idx_landmark_activity` ON `travel-sample` (activity)

WHERE type = "landmark"

CREATE INDEX `idx_landmark_country` ON `travel-sample` (country)

WHERE type = "landmark"If you execute this query it will run in ~100ms, examining the plan text shows that an IntersectScan is performed, and an IndexScan is run on each of the above indexes. The scan on idx_landmark_country returns 388 results and the scan on idx_landmark_activity returns 287 results, both of these are passed to the IntersectScan operator for a total of 675 records and then filters that down to 388 results.

{

"~children": [{

"#operator": "IntersectScan",

"#stats": {

"#itemsIn": 675,

"#itemsOut": 388,

...

},

"scans": [{

"#operator": "IndexScan3",

"#stats": {

"#itemsOut": 388,

...

},

"index": "idx_landmark_country",

},

{

"#operator": "IndexScan3",

"#stats": {

"#itemsOut": 287,

},

"index": "idx_landmark_activity",

}

]

}]

}Alternatively, if a composite index is used instead, this will result in a single IndexScan operation and be more performant. The same query using the index below will execute in ~17ms.

CREATE INDEX `idx_landmark_activity_country` ON `travel-sample` (activity, country)

WHERE type = "landmark"In general, a single wide index (composite index) which meets the criteria will be more performant than intersections on multiple singular indexes. Only consider intersection when the predicate usage is non-deterministic.

Tip 17: Avoid LIKE Statements

Oftentimes we need to find partial matches within a given index key and use a LIKE statement. This is useful and convenient syntax, however, this performs a range scan that depending on the use of % can be a range of the entire index and result in a lot of extra processing. For this example, we'll use the following index and base query:

CREATE INDEX idx_landmark_names ON `travel-sample` (name)

WHERE type = "landmark"SELECT name

FROM `travel-sample`

WHERE type = "landmark"

AND name LIKE '%Theater%'Execution Time: ~190ms

Now let's examine the various spans associated with the LIKE statement:

| Statement | Low | High | Inclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| '%Theater%' | "" | "[]" | 1 |

| 'Theater%' | "Theater" | "Theates" | 1 |

| '%Theater' | "" | "[]" | 1 |

Clearly, the second option 'Theater%' offers the more performant range scan as it is a targeted subset of the index key instead of the entire index. Optimizing your LIKE queries to only match on the righthand side offers some performance benefit, but this is not always a possibility.

A powerful feature of N1QL is that it can index individual array elements, not just individual scalar properties. While name is a simple string, we can use any of the available string functions to convert the string into an array (SPLIT, TOKENS, SUFFIXES, etc.) For this example, we'll use the SUFFIXES() function.

SELECT RAW SUFFIXES("Clay Theater")[

[

"Clay Theater",

"lay Theater",

"ay Theater",

"y Theater",

" Theater",

"Theater",

"heater",

"eater",

"ater",

"ter",

"er",

"r"

]

]As this returns all possible suffixes of a given string as an array, we can effectively index this array and now remove the left-hand % from our query providing a more efficient range scan.

CREATE INDEX idx_landmark_names_suffixes ON `travel-sample` (

DISTINCT ARRAY v

FOR v IN SUFFIXES(LOWER(name))

END

)

WHERE type = 'landmark'SELECT name

FROM `travel-sample`

WHERE type = "landmark"

AND ANY v IN SUFFIXES(LOWER(name))

SATISFIES v LIKE 'theater%'

ENDExecution Time: ~17ms

This query is now 11 times faster than the original. You should always consider the size of an array index, as in this case the larger the string the larger the array for each item and the larger the index size. Reference

Tip 18: Consider Array Indexes as an alternative to OR Statements

Many times we need to write a query that can satisfy "this OR that" and return results from either the left-hand or right-hand side of the OR. Lets take a common example where a user needs to login to an application with their "username" OR "email".

SELECT userId, pwd, firstName, lastName

FROM ecommerce

WHERE docType = 'user'

AND (

username = 'johns'

OR

email = 'johns'

)And we'll start with the following indexes:

CREATE INDEX `idx_username` ON `ecommerce` (username)

WHERE docType = 'user'

CREATE INDEX `idx_email` ON `ecommerce` (email)

WHERE docType = 'user'Viewing the explain plan of this query shows that a UnionScan is performed using two separate IndexScan operations on the idx_username and idx_email. A simple approach, in this case, would be to have the application construct two separate queries and inspect the input prior to issuing the query as an email pattern is trivial to validate, which would eliminate the UnionScan and result in a single IndexScan. This might not always be possible, so next, you might drop the previous indexes and attempt to create a single index to cover both username and email address:

CREATE INDEX `idx_username_email` ON `ecommerce` (username, email)

WHERE docType = 'user'But the query would fail, because a UnionScan is still attempted, it is just two scans of the same index. It would need to be rewritten as follows for the same index to use:

SELECT userId, pwd, firstName, lastName

FROM ecommerce

WHERE docType = 'user'

AND (

username = 'johns'

OR

username IS NOT MISSING AND email = 'johns'

)This is not an optimum approach either. While we only maintain a single index it results in a UnionScan and the range on the first index key is scanned completely.

Array indexes are very powerful and provide optimized execution of queries when array elements are used, something that is not possible with traditional databases. In this case, our data is not an array, but we can index it as one by creating a functional array.

CREATE INDEX idx_username_email_arr ON `ecommerce` (

DISTINCT ARRAY v

FOR v IN [LOWER(username), LOWER(email)]

END

)

WHERE docType = 'user'SELECT userId, pwd, firstName, lastName

FROM ecommerce

WHERE docType = 'user'

AND ANY v IN [LOWER(username), LOWER(email)]

SATISFIES v = 'johns'

ENDThe explain plan verifies that only a single DistinctScan is performed against our index. This query would only expect a single result but is performing a "FETCH" as the fields userId, pwd, firstName, lastName are not in the index. If we wanted to squeeze every last bit of performance we could cover the query with the index:

CREATE INDEX idx_username_email_arr_cvr ON `ecommerce` (

DISTINCT ARRAY v

FOR v IN [LOWER(username), LOWER(email)]

END,

userId, username, pwd, firstName, lastName

)

WHERE docType = 'user'Tip 19: Favor Equality Predicates over Ranges

Equality predicates are preferred and more performant than range scans, as a range is bounded by a low and high value, and the performance of the scan depends on how wide the range scan is. As an example, almost every application works with dates in some form or fashion, and are typically stored in either ISO-8601 (i.e. "2019-01-15T10:42:23Z") or Epoch time (i.e. "1547548943000") formats. Consider the following query and index to find all of the orders on a specific day:

CREATE INDEX idx_orderDate ON `ecommerce` (orderDate)

WHERE docType = "order"SELECT orderId, orderDate, orderTotal

FROM ecommerce

WHERE docType = "order"

AND orderDate >= "2019-01-15T00:00:00"

AND orderDate < "2019-01-16"This results in a range scan:

{

"range": [

{

"high": "\"2019-01-16\"",

"inclusion": 1,

"low": "\"2019-01-15T00:00:00\""

}

]

}However, if we create a functional index we can use a single equality predicate i.e. WHERE orderDate = "2019-01-15"

CREATE INDEX idx_orderDate_date ON `ecommerce` (SPLIT(orderDate, "T")[0])

WHERE docType = "order"SELECT orderId, orderDate, orderTotal

FROM ecommerce

WHERE docType = "order"

AND SPLIT(orderDate, "T")[0] = "2019-01-15"Tip 20: Implement Index Replication

Indexes can (and should) be replicated across cluster-nodes. This ensures:

- High Availability (failover): If one Index-Service node is lost, the other continues to provide access to replicated indexes.

- High Performance: If original and replica copies are available, incoming queries are load-balanced automatically across them. This is contrary to the data service, where document replicas are "passive", index replicas are "active".

Prior to Couchbase Server 5.0, the only way to have "replica" indexes was to have the same index definition, but with a different name and manually place the indexes on different hosts.

CREATE INDEX productName_index1 ON bucket_name(productName, ProductID)

WHERE type="product"

WITH { "nodes": ["host1"] }

CREATE INDEX productName_index2 ON bucket_name(productName, ProductID)

WHERE type="product"

WITH { "nodes": ["host2"] }As Couchbase Server 5.0+ index replicas are specified by using the WITH clause, simply specify the num_replica value.

CREATE INDEX productName_index1 ON bucket_name(productName, ProductID)

WHERE type="product"

WITH { "num_replica": 2 };The only requirement is that the number of nodes in the cluster running the Index service is greater than or equal to {num_replica} + 1. Replicas can also be created by specifying the destination nodes of the index:

CREATE INDEX productName_index1 ON bucket_name(productName, ProductID)

WHERE type="product"

WITH { "nodes": ["node1:8091", "node2:8091", "node3:8091"] }Additionally, both num_replica and nodes can be specified as long as num_replica is equal to the length of the nodes array + 1.

CREATE INDEX productName_index1 ON bucket_name(productName, ProductID)

WHERE type="product"

WITH { "num_replica": 2, "nodes": ["node1:8091", "node2:8091", "node3:8091"] }Whenever a CREATE INDEX statement is issued, the default number of index replicas to create is 0. This value can be changed, such that anytime a CREATE INDEX is performed there is no need to specify the WITH clause and replicas will be created automatically.

curl \

-u Administrator:password \

-d "{\"indexer.settings.num_replica\": 2 }"

\

http://localhost:9102/settingsTip 21: Defer Index Builds to share DCP stream

When a CREATE INDEX statement is issued, each document in the keyspace must be projected against the index and by default, this is a synchronous operation. Meaning it will block until the index is built 100%, at which point in time the index will be updated asynchronously by any future mutations. This can be cumbersome and time-consuming, especially when managing many indexes.

In Couchbase, there can only be one index build process going on at a time. However, that does not mean that there can only be one index being built at a time. N1QL allows you to define the index but defer the actual building of the index to a later point in time, this is done using the WITH { "defer_build": true }.

CREATE INDEX `def_sourceairport` ON `travel-sample`(`sourceairport`)

WITH { "defer_build":true }

CREATE INDEX `def_city_state` ON `travel-sample`(`city`, `state`)

WITH { "defer_build":true }The indexes are in a "Created" state and not eligible to be used until they are built. To build multiple indexes at the same time a BUILD INDEX is used.

BUILD INDEX ON `travel-sample` (def_sourceairport, def_city_state)The BUILD INDEX is asynchronous by default and has the primary benefit of allowing each index build to share the same DCP stream, and each document that is projected for the index build only has to be retrieved once instead of once per index.

Tip 22: Consider the Projection Selectivity of the Index

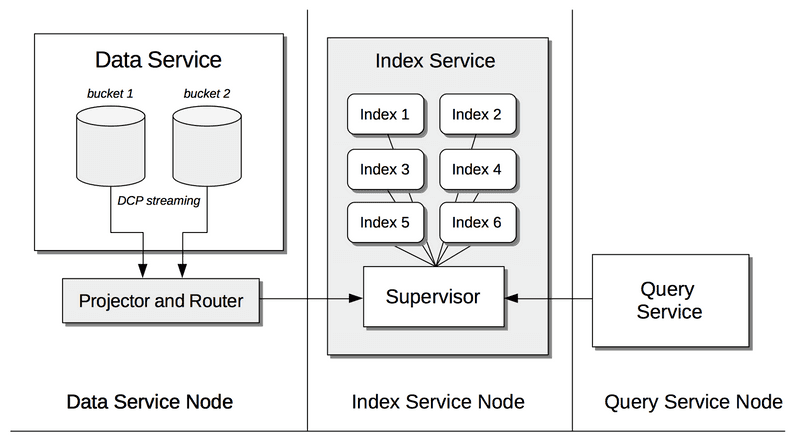

The Data, Index and Query service all work together to perform N1QL queries and manage indexes. While the bulk of index processing resides with the Index Service, there are two components of indexing that actually reside within the Data Service. These are the "Projector" and "Router" processes, which are responsible for projecting every data mutation against each index on the bucket and communicating those mutations to the "Supervisor" process on the Index Service.

This is roughly the # of documents that would qualify for the index divided by the total # of documents in the bucket.

For example, a bucket with 1,000,000 documents, and 100 of those documents were "config" documents, if we created an index with the predicate of WHERE docType = "config" the Projection Selectivity is 0.10%. Conversely, if you created an index on just docType for example and every document in the bucket has docType the Projection Selectivity is 100%.

Both of these are on the extreme ends of the spectrum, the first will only satisfy projection 0.10% of the time and there would be many wasted CPU cycles on unnecessary projection and you may want to consider an alternative access pattern. Additionally, having a Projection Selectivity of 100% is also not performant as every mutation meets projection and results in an update to the index. There is not a set number, as it will be specific to each data set, but understand the implications of unnecessary projection.

Tip 23: Combine Multiples Scans Using CASE Expressions

Often, it is necessary to calculate different aggregates on various sets of documents. Usually, you achieve this goal with multiple scans on the data, but it is easy to calculate all the aggregates with a single scan. Eliminating n-1 scans can greatly improve performance.

You can combine multiple scans into one scan by moving the WHERE condition of each scan into a CASE expression, which filters the data for the aggregation. For each aggregation, there could be another field that retrieves the data.

The following example asks for the hotels which have free internet or free breakfast or free parking. You can obtain this result by executing three separate queries:

SELECT COUNT(*) FROM `travel-sample` WHERE type="hotel" and free_internet=true

SELECT COUNT(*) FROM `travel-sample` WHERE type="hotel" and free_breakfast=true

SELECT COUNT(*) FROM `travel-sample` WHERE type="hotel" and free_parking=trueTotal time = 119.23 + 121.63 + 118.71 = 359.57ms

However, it is more efficient to run the entire query in a single statement. Each number is calculated as one field. The count uses a filter with the CASE expression to count only the rows where the condition is valid. For example:

SELECT COUNT(CASE WHEN free_internet=true THEN 1 ELSE null END) cnt_free_internet,

COUNT(CASE WHEN free_breakfast=true THEN 1 ELSE null END) cnt_free_breakfast,

COUNT(CASE WHEN free_parking=true THEN 1 ELSE null END) cnt_free_parking

FROM `travel-sample`

WHERE type="hotel"The query takes 250 ms, shaving off an entire 100ms off the total time taken, not to mention the network calls, processing etc. that it would take while querying it from the application side.

This is a very simple example, larger datasets will show larger variances. There could be ranges involved, the aggregation functions could be different, etc.

Tip 24: Make your Documents Index Friendly

Different access paths can determine the optimum structure of your documents. When you are leveraging N1QL, you will want to ensure your documents are "index friendly". Ensure all documents have a consistent docType (or equivalent) attribute. This allows for efficient filtering during indexing, querying or both.

{

"docType": "user",

...

}If you're performing some processing on an array in the document, instead of performing that processing in the query consider storing a pre-computed value in another attribute (e.g. total, average, score, etc.)

{

...

"scores": [

78,

97,

23,

...,

43

],

"scoreTotal": 2392,

"scoreAvg": 77.6,

"scoreMin": 23,

"scoreMax": 99

}If an attribute name is dynamic or unknown, it's OK for KV access but not practical from an indexing standpoint. Below the first example is simply not practical to index or search if that object had every single language listed in there, you would need one index per language.

Bad for Index/Querying:

{

"Greetings": {

"English": "Good Morning",

"Spanish": "Buenos días",

"German": "Guten Morgen",

"French": "Bonjour"

}

}Good for Index/Querying:

{

"Greetings": [

{

"Language": "English",

"Greeting": "Good Morning"

},

{

"Language": "Spanish",

"Greeting": "Buenos días"

},

{

"Language": "German",

"Greeting": "Guten Morgen"

},

{

"Language": "French",

"Greeting": "Bonjour"

}

]

}Tip 25: USE INFER to understand your dataset

Couchbase buckets are a logical namespace made up of one or more types of documents/models. Understanding these models and their underlying structures can provide additional opportunities for performance and tuning. N1QL supports the INFER statement, that is statistical in nature. It analyzes a bucket through sampling and returns results in JSON Schema format.

INFER `travel-sample` WITH {

"sample_size": 1000,

"num_sample_values": 5,

"similarity_metric": 0.6

}For each identified attribute, the statement returns the following details:

| Attribute | Description |

|---|---|

| #docs | Specifies the number of documents in the sample that contain this attribute. |

| %docs | Specifies the percentage of documents in the sample that contain this attribute. |

| minitems | If the data type is an array, specifies the minimum number of elements (array size). |

| maxitems | If the data type is an array, specifies the maximum number of elements (array size). |

| samples | Displays a list of sample values for the attribute found in the sample population. |

| type | Specifies the identified data type of the attribute. |

Tip 26: META() properties such as CAS and Expiration can be Indexed

CAS or Compare-and-Swap values are used as a form of optimistic locking for document mutations. The CAS value can be returned from a N1QL query by calling the META() function and referencing the META().cas value.

If you are leveraging CAS operations and attempting to cover your queries, this value will need to be added to the index.

Tip 27: Beware of the Scan Consistency Level

N1QL indexes are updated asynchronously after a mutation has occurred on the data service. While key-value operations against the data service are strongly consistent, and while index updates are extremely fast (usually <1ms), because of the asynchronous nature they are "eventually consistent".

N1QL allows you to specify the Scan Consistency level to use for a query. There are three possible values:

- Not Bounded: Is the default and the fastest. It says to return the results that are currently in the index, regardless or not if there are items in the queue waiting to be indexed.

- Request Plus: Is the opposite and slowest of the scan levels. At query time it will wait for all indexes to catch up to their highest sequence numbers. The benefit of this slower scan level is it allows you to Read Your Own Write (RYOW) but could take some time if the system is under heavy write load.

- Statement Plus / At Plus: Is unique compared to the other two scan levels and requires

mutationTokensto be enabled before it can be used. This causes a few extra bytes of information to be sent back to the SDK whenever a mutation occurs. The mutation tokens are then passed to the N1QL query and the query will wait for at least those tokens to be indexed prior to proceeding.

// enable mutation tokens

CouchbaseEnvironment env = DefaultCouchbaseEnvironment

.builder()

.mutationTokensEnabled(true)

.build();

// mutate a document and save the mutation

JsonDocument written = bucket.upsert(JsonDocument.create("mydoc", JsonObject.empty()));

// written.mutationToken() ==

// "mt{vbID=55, vbUUID=166779084590420, seqno=488, bucket=travel-sample}"

// pass the mutation to the query

bucket.query(

N1qlQuery.simple("select count(*) as cnt from `travel-sample`",

N1qlParams.build().consistentWith(written))

);There is a price to pay for using a query scan consistency such as Request+ or Statement+. See if you can achieve the desired result by key-value Access, especially if it's a single document or a handful of documents which can be obtained via a multi-get.

Tip 28: Use IN instead of WITHIN

The IN operator specifies the search depth to only include the current-level of the array on which it is operating against. Whereas the WITHIN operator specifies the search depth to include the current level of the array it's operating on and all of the children and descendant arrays indefinitely.

The use of WITHIN can have unexpected performance consequences if used incorrectly, by recursively iterating through all arrays of a given property.

Tip 29: Cancel Long Running or Problematic Requests

Active N1QL requests are stored in the system:active_requests catalog, if the result of the query is greater than 1s it will be stored in the system:completed_requests catalog, otherwise it is discarded. If you need to cancel any active requests, you can issue a DELETE statement against the system:active_requests keyspace effectively canceling the query.

DELETE

FROM system:active_request

WHERE requestId = "..."Tip 30: Cleanup system:completed_requests

The system:completed_requests is extremely useful with identifying slow performing and resource intensive queries. As you continue to iterate through each of the queries and optimize them, you no longer want to see that same query in system:completed_requests. You can delete records from the system:completed_requests catalog, just as you would with any other keyspace.

DELETE

FROM system:completed_requests

WHERE requestId = "..."

DELETE

FROM system:completed_requests

WHERE statement = "SELECT DISTINCT type\nFROM `travel-sample`"Tip 31: Initially Design Queries / Indexes on an Empty Bucket

Designing, building and iterating on indexes against a bucket with a large number of documents can be time-consuming. When initially designing queries and indexes, if possible, execute them against an empty bucket until you're satisfied with the explain plan.

Tip 32: Remove Unused Indexes

Proactive monitoring is critical to any application, not only should you be actively monitoring indexes and their usage to identify potential growth needs, you should also be monitoring and identifying indexes which are not used and can be dropped.

Tip 33: Set clientContextID option in the SDK

The clientContextID is a user-defined identifier query option that can be sent to the query service from the SDK. This is not used by Couchbase for anything, however, it is stored in the system:active_requests and system:completed_requests. This can be a true application requestId/genesisId generated by the application, or some type of application identifier that can be later used for debugging or tracking down specific queries related to a given application or request.